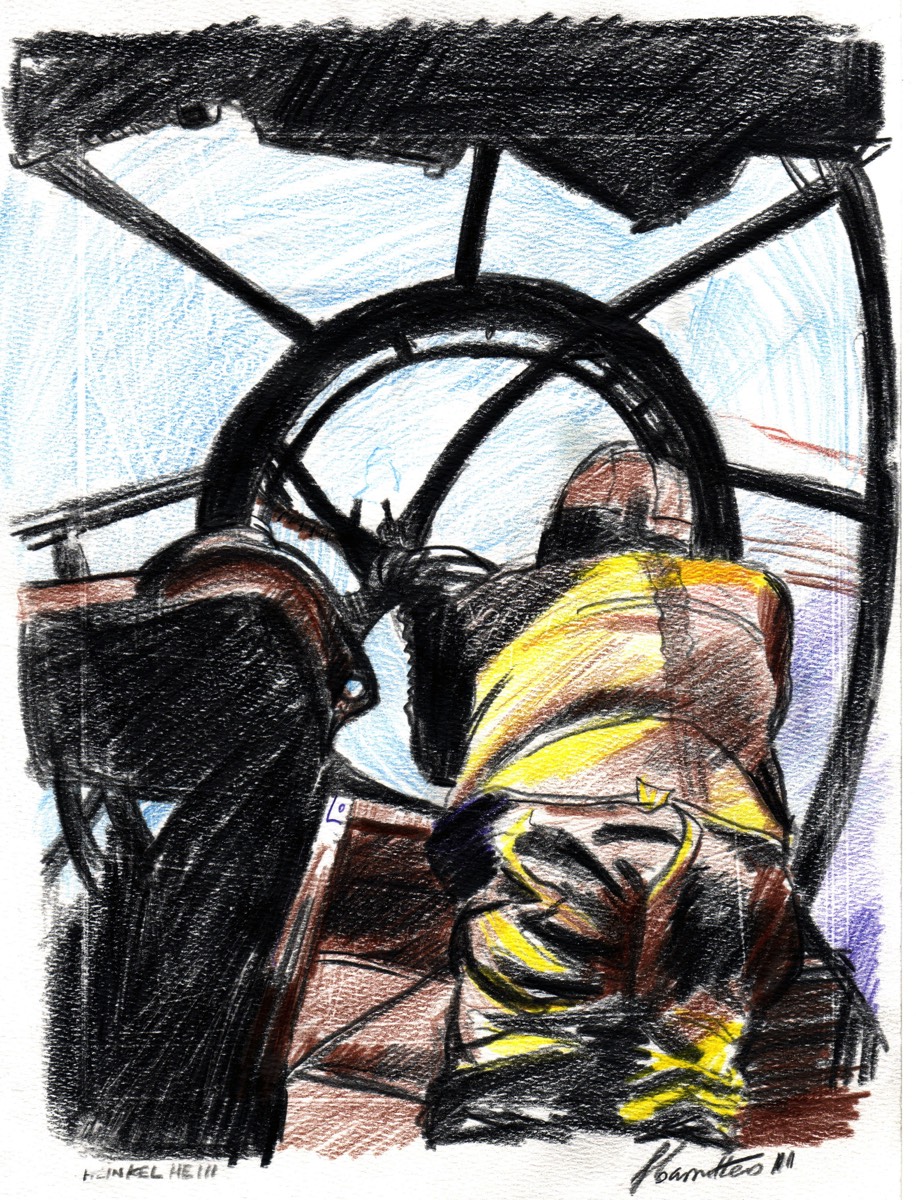

A Heinkel front gunner.

Artist: Stuart Carruthers.

Air Raids in East Lothian

Thanks largely to its rural nature and its relative dearth of military or industrial targets, East Lothian was not heavily bombed during the war. Nevertheless, between September 3rd, 1939 and March 25th, 1943, three parachute mines and 200 High Explosive bombs were dropped on the county (sixteen of which did not explode). The Luftwaffe mirrored the RAF’s lack of success at hitting targets in the early stages of the war and by 30th August, 1940, it had dropped fifty-five HE bombs for the reward of injuring one soldier on Berwick Law (bombed on 25th August, 1940) and one sheep (killed on Chapel Farm, West Fortune, on the 30th August of the same year).

The overwhelming majority of bombs dropped on East Lothian fell on fields and farmland and did little or no damage and it must be concluded that in most instances this was the result of pilots dropping their loads on an ad hoc basis, perhaps because of the attention of fighters, perhaps because of an unwillingness to face the stronger defences around Edinburgh, perhaps as simple nuisance attacks. The North Berwick and Berwick Law area was hit by thirteen bombs during this period, probably because of its prominent position jutting out into the Forth. The Co-Op Store, just two days short of opening on Lochbridge Road, was hit and damaged on the 3rd November 1940.

Eleven bombs and a mine were dropped into the sea or on beaches along the coast of the county. East Linton was the target of one bomb and four UXBs (unexploded bombs), one of which hit the New Bridge on the 25th October 1941. RAF Drem was attacked on three separate occasions and minor damage was done by the total of ten bombs dropped. In addition, Dunbar, Tranent, Archerfield Golf Course, Prestonpans and Whitekirk, all received the Luftwaffe’s attention over this period.

A number of towns, villages and farms were machine gunned by aircraft including West Barns, East Linton, Dunbar, Tranent and Innerwick Railway Station. The latter attack, on the 16th August 1941, was one of the more serious attacks as one railway worker, Robert Faichen, was killed and three of his workmates wounded.

However, it was Haddington’s lot to suffer the most damaging raid of the war in East Lothian.

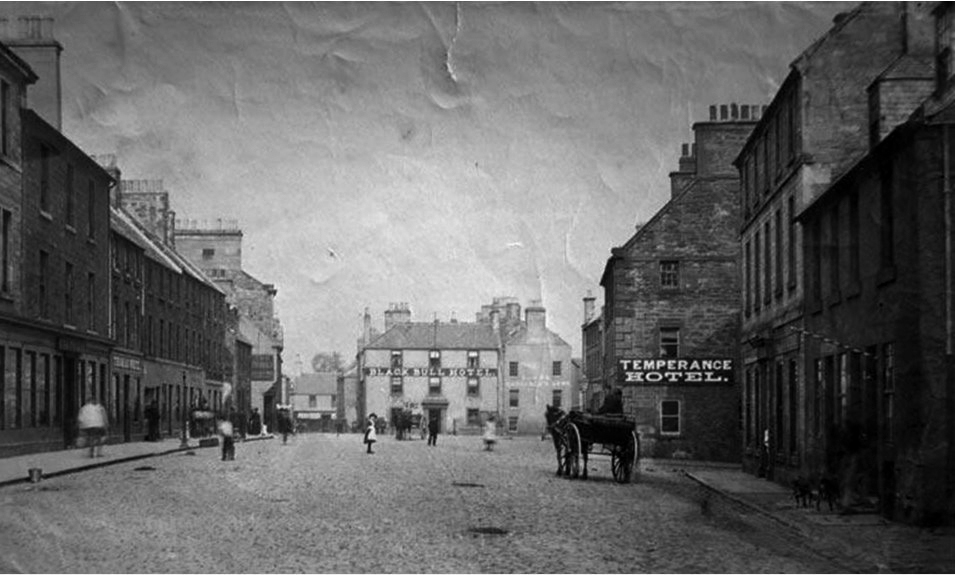

Haddington’s Air Raid, Monday, 3rd March, 1941.

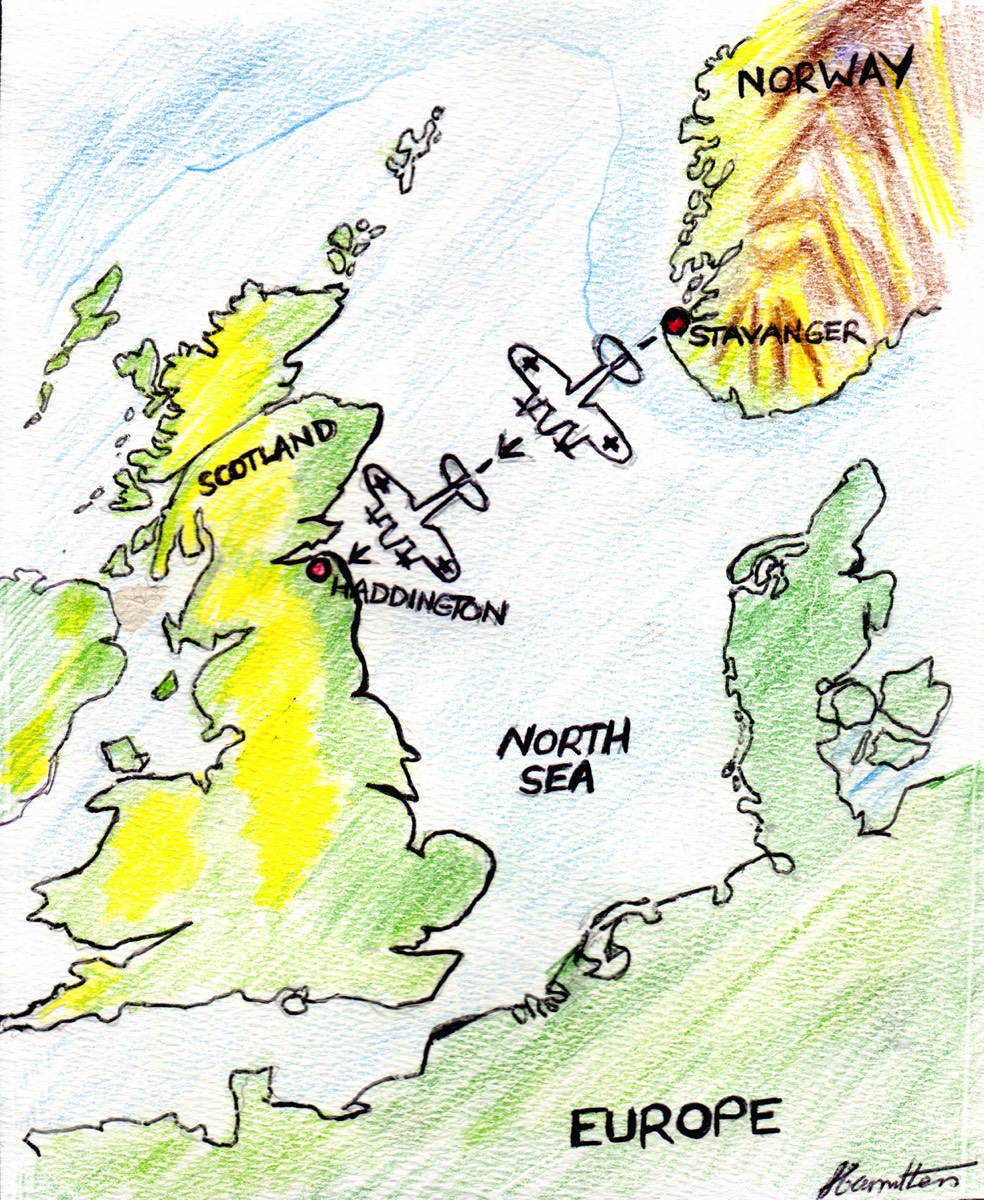

Likely route of the Haddington raider

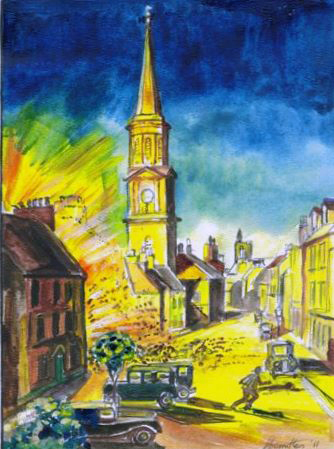

Artist: Stuart Carruthers.

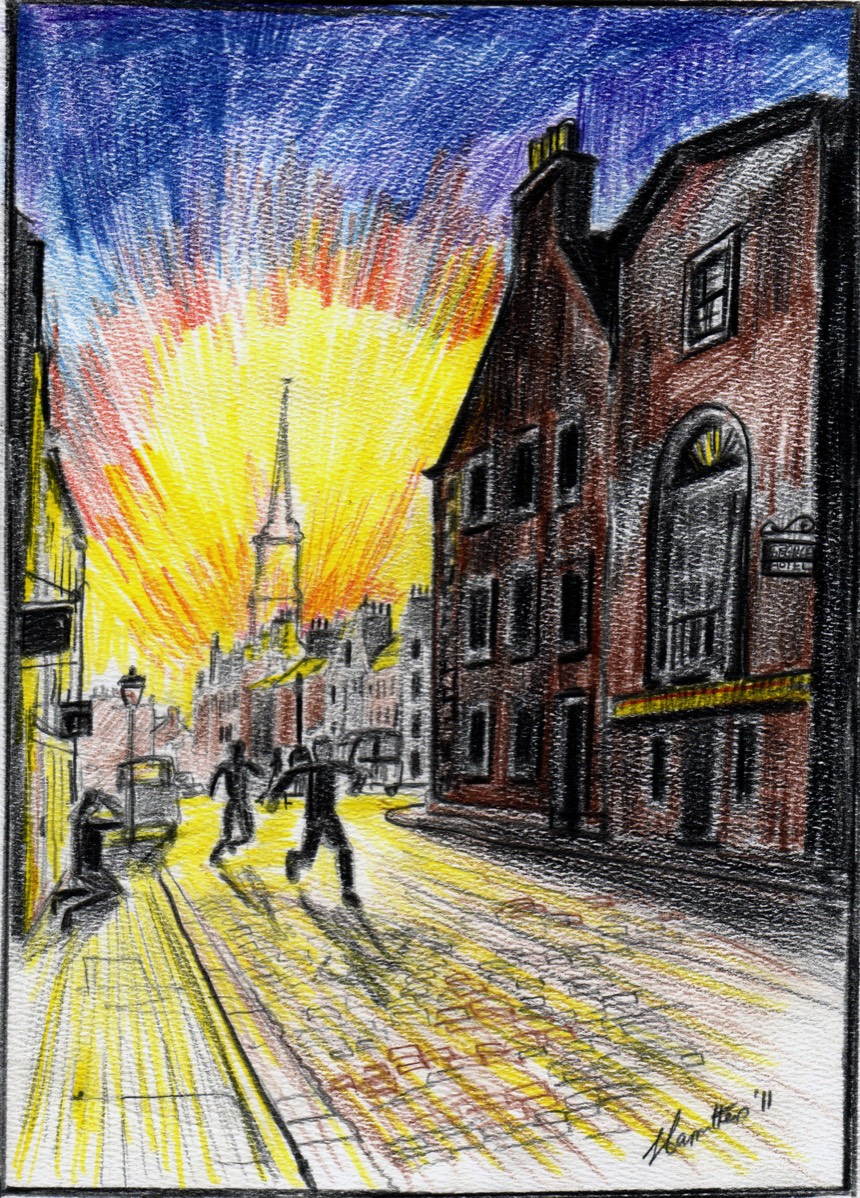

Haddington High Street during the raid

Artist: Stuart Carruthers.

Why Bomb Haddington?

In the late winter of 1941 Haddington was a small, rural county town possessing few of the usual military, industrial or communications features which could have drawn the attention of Luftwaffe planners and it had seen nothing of the Blitz experienced by other less fortunate towns and cities. Its inhabitants had become used to being overflown, but not attacked.

Its bombing by a single aircraft on Monday, the 3rd of March 1941, was unlikely to have been as a result of a planned raid. Rather Haddington presented a target of opportunity willingly grasped by a pilot keen to avoid the defences further west and keen to do some damage after the long flight from Norway. It is possible that this aircraft, a Heinkel III, probably from KG26 operating from Stavanger, had already dropped mines into the Forth. Had the German air force been intent upon a specific target, in other words here on a planned raid, it is unlikely the work would have been left to only one aircraft.

Claims have been made that this raid was somehow part of the Clydebank raids, but they did not take place till the 13th and 14th March, so this is highly unlikely. Other have pointed out that a military convoy was proceeding towards Amisfield camp at much the same time and it is possible that this drew the pilot’s attention to Haddington itself. After all, Air Raid Wardens at their post on the (old) A1 reported at 21.00 hours that Amisfield Park was looking like “...fairyland...” and the bombs were dropped five minutes later. Incontrovertible evidence as to why the town was bombed is unlikely to surface, as the records of the Luftwaffe unit involved have been lost, most likely in bomb damaged Berlin or even in the frozen wastes of Russia.

Interestingly, other German bombers were in action over East Lothian that night as the official record of bombs dropped in the county stated that, in addition to the action over Haddington:

“Five HE bombs were dropped in Thurston Glen, five miles south-east of Dunbar. Four exploded and one remained unexploded. The UXB was detonated by the Bomb Disposal Squad on 13th March...no damage - no casualties [and] Three HE bombs [were] [ dropped in open country near Stenton. No damage - no casualties.”

John M. Armstrong, an eyewitness, maintained that “...on or about the same night there was excitement in East Linton, a load of incendiaries was dropped on the eastern slopes of Traprain, where they set a wheat field on fire, and five HE bombs were then dropped 300 yards north east of a searchlight position at Birkiemuir, south of Stenton.”

The Bombing

Half an hour after the sirens had wailed out their warning at 8.30pm, the Luftwaffe bombed the town. The Heinkel first dropped incendiaries which fell harmlessly across the lower fields of Amisfield Farm. Its main load of six one hundredweight HE bombs was then dropped across the town from east to west towards the Town House: the Victoria Terrace and Market Street areas took the brunt of the attack.

The New County Cinema, yards from the first bomb.

Bomb 1: The ruins of 1 Victoria Terrace, Pringle’s home and furniture shop.

Iain Hutchinson on the left.

Eyewitness: Iain Hutchinson - Resident In Victoria Terrace

“Our house wasn’t directly on the corner; our house was the next one along and my mother and my aunt were in the kitchen making the supper and my grandmother and I were in her little sitting-room blethering. Our first warning of the raid was the siren going off and my father and my brother shot off to the Fire Station because they were both in the NFS and that left just ourselves. I don’t remember any great bang, though I think I may have heard the whistle of bombs coming down, but the first sort of sound that I can really remember was the sound of something like plaster falling down the back of the wall. It was, in fact, Bob Pringle’s house which was above the shop and had been hit and collapsed. This was literally the house next door to ours, there being just a landing between us.

There was now no way out of our house. We hadn’t been thrown to the floor, there was no shaking or problems like that. In fact, I was in a semi-recumbent posture lying on a sofa and my grandmother was sitting in her chair on the other side of the fireplace. The slab at the back of the fire came in and the gaslight started to flicker so I got up and turned the gas off and poked the ashes back into the fireplace.

My mother and aunt went to the front door to see what was wrong and my aunt went out but, of course, there was no staircase and no landing, so she fell straight down and my mother quickly followed her, landing on top and gave her concussion which sent her to hospital. My mother was remarkably unscathed. My grandmother was all set to go out of the front door to see what had happened but I grabbed a hold of her because, by this time, my eyes had got accustomed to the dark and I could, in fact, see flames up the street and I shouldn’t have been able to see up the street because Bob Pringle’s house should have been there!

The rescue people came along and put a ladder up to the window and with some difficulty I managed to get my grandmother down this ladder, because, you know, it’s not something she did every day in life. I also collected the suitcase with all our birth certificates, insurance, you name it, and the gas masks and we went down. We were housed in the Forrester’s Hall just along the road. After some time, my mother joined us there, my aunt being still in hospital. My father, by this time, was fighting the fire which I’d seen through the front door, the one up at Baillie’s shop, the shop which was used by the army as a store for everything, ammunition, acetylene bottles, all sorts of things and these were going off bang, bang, bang. So, he was busy fighting that fire, not knowing just how we were down at the other end of the street.

The next day, like all boys, we went raking along the banks of the Tyne [downstream of the Victoria Bridge] and we found a lot of incendiary bombs. They were all burnt out apart from one which was lying in shallow water in the river. I picked it up and it appeared to be untouched and I took this back and showed it to my father and said, ‘Look it’s just like the one you made’, because he’d made a dummy one to show people what incendiary bombs looked like. ‘It could have gone off,’ he said. ‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘I banged it against the wall like you do with practice ones and nothing happened.’ Bang! He gave me a clip on the ear and that was our Counselling session. A day to remember or, in fact, a night to remember.”

Eric Groome (on the left) 1941.

Eric Groome, second from the right, on the site of Baillie’s shop, c1998.

Eyewitness: Eric Groome, Auxiliary Fireman

“It began in the picture house. We’d just seen the first picture when the manager came on the scene and jumped onto the stage and announced, as he had to, that there was a raid on. As I was on duty I upped and ran as hard as I could and as I was passing Laidlaw’s window the whole of the window shattered and fell out behind me. I reckoned that if I’d been walking, I’d have been in the blast. The poor soul who was across the street, who was John Moggie, he got the direct blast and it killed him outright because he was blown from the bottom of the staircase right to the top.

So, I ran to the pump yards and we harnessed up the three pumps and then we had to play the hoses on the roof, then the roof exploded. Inside were barrels of oil, tyres, small arms .303 ammunition, hand grenades, small two-inch mortars, flares, everything attached to the army. It was an army dump. Luckily the explosions were going upwards because of the strength of the stone walls which guided the blast upwards. If it had been a spread no one would have been safe. The next morning it was a case of it all being roped off but, prior to that, the night before the street had been packed with sightseers who had never experienced explosions in their lives before.”

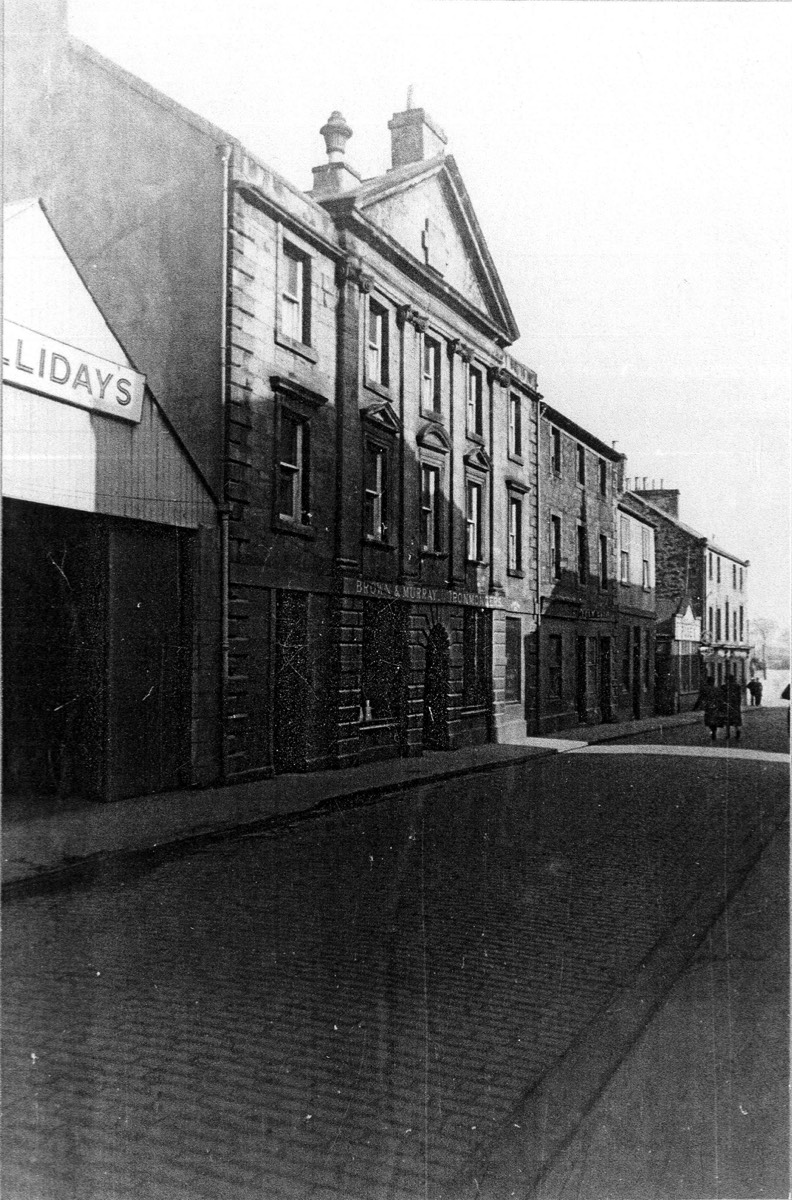

Brown and Murray, Market Street: 2nd bomb fell to its rear and 3rd bomb fell by Halliday’s garage which stood where the white building to its left now stands.

Bomb fragment found in Market Street.

Halliday’s garage to the left of Brown and Murrays.

Bomb 3 fell in the street by Halliday’s Garage and bounced off its door before exploding in the street. This bomb killed a soldier, Sergeant J. Matheson of the 52nd Division, who was sheltering in a doorway.

Bomb 4: Site of the old Courier Printing Works and Office on the corner with 16 Market Street to its right.

Scott Anderson in front of the door to

his former home in 16A Market Street.

Eyewitness: Scott Anderson

Aged six, Scott lived in the flat at the time and was fast asleep in his bedroom. His first memory is of the noise and commotion in the street outside and of then being told by his father that he would have to leave as there was a bomb outside. He was wrapped in a blanket and carried out of the flat by his father who had the anxious task of having to step over the bomb to escape! His uncle carried his brother out after him. Scott emerged into Market Street to the noise and flames from the fires by Baillie’s shop. He was taken into the Black Bull Hotel past another crater. The bomb was given a careful inspection and was later carried away by Scott’s father and an Air Raid Warden. Scott admits that he was, ‘...lucky, extremely lucky.’

According to J. Annand this bomb did considerable damage to the roof of the Courier building and the resulting debris lay all around in the Linotype room, including all over the printers. Staff covered the machines as best they could and so provided some protection from the rain now falling through gaps in the roof. The next morning a large tarpaulin was obtained and stretched across the hole and the machines given a thorough clean. The next edition of the Courier duly appeared on time.

Backing on to Baillie’s and entered via the High Street was the town’s telephone exchange in an upstairs room. There, the operator, Miss Agnes Chirnside, had come on duty as normal at 20.30 hours. She was due to remain there till relieved at 08.00. She was often assisted by her sister, Mrs Birrell, a policeman’s wife, who came unofficially to keep her company through the long, dark hours. Despite the danger and the heat from the building beyond in Market Street, heat sufficient to set the exchange’s curtains on fire, Agnes bravely continued at her vitally important work. She was, after all, the hub of the emergency communications in the town and had to keep all the various emergency services in touch with each other. The fire in the curtains was extinguished using a Stirrup Pump. Folklore has it that she had to ask callers to speak a little louder because of all the noise!

Damage in the vicinity of the bombs was quite extensive, all the windows in Market Street, for example, being shattered. The corner of Victoria Terrace and Hardgate was later occupied for many years by the Ideal Garage and plans are afoot to rebuild on the site. The site of Baillie’s shop remained a bomb site, given over to gardens, for many years until flats and business premises were constructed in 2000 and the space restored to something approaching its former use.

Former site of Baillie’s Gift Shop during clearance prior to rebuilding in 2000.

Tollbooth Gate, No’s 56-59 Market Street rebuilt upon Baillie’s site in 2000.

Eyewitness – Fay Reilly

“I remember that night very well. My brother, sister and I spent all our summer holidays with my Aunt, Uncle and Cousin. My Uncle, Jimmie Grant, worked for Richard Baillie and he had a flat above the garage at 52 Market Street. We had listened to the radio the Sunday morning when War was declared. As a young child of twelve it didn’t mean too much for me although my Aunt and Uncle were very worried. Alex, my Brother, and I were not allowed to go home to Edinburgh. It was thought that we would be safer in Haddington. We were sent to school at the ‘Knox’. My brother eventually went home in 1940.

The night of March 3, 1941 was quiet. My Aunt’s Auntie had come over from the High Street to visit her Sister, my Aunt’s mother, who lived with us. As it was a quiet night my Aunt said the ‘Chip Shop’ was open and I could go for ‘Chips’. As I was about to go my Uncle came upstairs and asked me where I was going – I said, ‘Chip Shop’ – and he said ‘No’. He was looking from the skylight in the office next door at a plane caught in the searchlights. I was not to go out.

He left again. My Aunt said – just wait five minutes and then you can go. I did. I went down and crossed the High Street, queued up, got chips and hurried back. I just got back and was handing Aunt Lizzie the packet when there was the most awful dull sound. The packet of chips flew, and my Aunt’s mother was thrown into the fireplace. There was another and suddenly Aunt Lizzie said, ‘We are being bombed’. She was crying and I started to cry. She looked out of the Blackout Curtain and the place looked as if the street was on fire.

Uncle Jimmie rushed up and said, ‘Get into the back of the house’. We just stood in a daze. Auntie Lizzie was crying and saying, “Where is James?” Uncle Jimmie came back and said we had to get out. Somehow, we did. We were taken to the Bank Manager’s house in High Street. We were there for I know not how long. Eventually someone said I was going to another uncle and aunt for the night. All I remember is getting into a car.”

Eyewitness - Kenneth J Vert Brown

“The evening of the 3rd March 1941 I was in the Town Hall, Haddington, with my mother and father rehearsing for a concert. During rehearsal the siren sounded and my father (Ken) left to do his duty as an Air Raid Warden in Davidson Terrace, leaving mother and myself to continue rehearsal. I remember hearing the aircraft. It seemed to come from the west [sic] over the Town Hall. This was followed by the sound of an explosion. All the lights were then put out and we left the building as soon as possible. We then walked home. Father was pleased to see us. Baillie’s building was well alight, and we were advised to leave the area by the Police.

The following day I went down the town to see the damage. The Toy Shop and Radio Shop had been destroyed. The corner, at the bottom of Market Street, with the furniture shop looking like a collapsed pack of cards – now a Petrol Station. A well-known lady, who had lost her leg prior to this date, was found in Market Street. She was discovered by a passer-by, who was very worried about the lost leg and had evidently shouted for help. It was soon discovered that it was an old injury and the lady, who lived nearby, was helped home.”

Air Raids In Prestonpans

Eyewitness - J.H. Miller (Lt. Commander, Royal Navy, Jan. 1949 - April. 1983) writing in 1998

“Prestonpans featured early in the war and I like to think the first air raid on the United Kingdom occurred on the 16th October 1939 when I was a pupil at Prestonpans Primary School. No air raid warning had been given and the pupils were enjoying playtime when this low-flying German aircraft appeared over the sports field with three Spitfires flying astern and pumping lead into the intruder. The teaching staff were frantic and trying hard to shepherd us all back indoors but to no avail. If I can recall correctly the sports field was strewn with spent bullet cases. The aircraft was brought down off Port Seton and the local fishermen used to complain bitterly when their nets snagged on the wreckage.

My father had joined the Auxiliary Fire Service and during raids he and two neighbours manned a fire watching post adjacent to our house armed with their stirrup pump. On those days during night raids, the family was awakened, and we were mustered under the stairs while father assumed his fire watching duties outside. I remember a night raid early in the war when we were summonsed outside by my father to observe the spectacle of a German aircraft caught in the searchlight beams and the streaks of tracers from pursuing aircraft. I suppose in the later war years we had become a little complacent and spent the air raid nights tucked up warmly in our beds and were unaware of events.

Prestonpans had two bombs [fall on it] during the war. In March 1941 we were again summonsed outside to see the western sky which was ablaze with light as Clydebank was blitzed. There was the continuous hum of the German aircraft engines as they headed west as we huddled in our cupboard under the stairs. My mother was attending a concert in the Town Hall as we sheltered with our aunt, two sisters (aged thirteen and five) and myself. My eldest sister had suggested making a cup of tea and as she left the cupboard there was this sharp whistle and loud bang and the shock waves of the blast threw her against the back door. Tea was quickly forgotten!

The bomb had exploded alongside the main Edinburgh to King’s Cross railway line on the south side. Whether the pilot was shedding his load or trying for the night train I have never managed to establish, but the site of the explosion was behind the old Meadowmill tenement block (since demolished) and near the 1745 memorial. Needless to say, at first light all the local schoolchildren were out searching for shrapnel. The reaction of my younger sister was quite amusing as she tried to simulate the whistle of the bomb, as was the reaction of my aunt whose in-laws resided in Portsmouth where they were showered with these bombs regularly.

Bomb number two was a more tranquil affair and I am unsure of the date. It was a dusky Sunday autumn evening and there had been no air raid warning. ...the air raid siren for the area was situated at Preston Links Colliery and there was a strong south westerly breeze so the warning sound may have alerted the Cockenzie and Port Seton areas only. As was the miners’ wont and as the police were nowhere to be seen, they had assembled for their gambling session of ‘Pitch and toss’. As children we were out playing when there was this whirring noise followed by a bang. The miners scattered, leaving their ill-gotten gains on the deck and as children we helped ourselves to the proceeds before being summonsed indoors. The bomb fell on the slopes behind Bankton Farm and the following day we found the crater in a potato field.”

Protection Against Air Raids

Few air raid shelters had been constructed in East Lothian prior to the war but many were constructed throughout the county during it. Below are some of those built in Haddington. many of them in fairly close proximity to the military facility (much used by the Poles to store and repair their tanks) which stood on the ground now occupied by the Library Headquarters on Dunbar Road. These three examples illustrate the wide variety of size and design of air raid shelters.

Air raid shelter off Dunbar Road.

Air raid shelter in Baird Terrace.

Air raid shelter, Haddington.

Machine Gun Attacks

On a number of occasions German aircraft attacked ground targets by machine-gunning them. Such attacks were of little military value and were more in the nature of nuisance attacks. Four such attacks were reported between July 1940 and March 1943: the first during the hours of darkness on the 9th October, 1940, when Dunbar, Tranent and their surrounding areas were attacked. The second came soon after on 26th October, 1940, when East Linton was shot up. Neither attack resulted in casualties. The third such attack, however, did. On the 16th August, 1941, a fatal attack was made on workers on the railway line at Innerwick. Three bombs had been dropped nearby (all UXBs) and the aircraft then shot at the workers injuring five of them and killing one, a Relayer, Robert Sharp Faichen, aged sixty-two. The final reported attack occurred on the following day when an aircraft machine-gunned West Barns Farm and succeeded in damaging a few tiles on the Farm Steading roof.

The painting below illustrates a JU88 (portrayed perilously low) firing on Preston Mains Farm workers clearly engaged in threshing.

Preston Mains Farm workers being attacked by a JU88’s machine gunners.

[Artist: Phyllis Fraser]

Eyewitness - Elizabeth Leslie describes the attack on Preston Mains Farm.

“I was nine years old on 16th October 1939. That afternoon I collected my bike from Dod Dowrie’s blacksmith’s shop after school as I used to leave it there. I was cycling home to Preston Mains. This would be around 4.15pm when I heard an aircraft coming. I could not see it at first, but the sound was quite different [from our own]. When I looked across the field, I saw this plane, a JU88. It had a big cross on its side and a Swastika on the tail. I could also see the men inside with their close-fitting leather helmets on. They were flying very low.

Just then they began firing at the travelling threshing mill which was working in the stack yard at Preston Mains Farm. By this time, I had jumped off my bike into the hedgerow at the side of the road. I just didn’t realise what was happening. It was only later when you thought about it: somebody could have been killed. The people who had been working at the mill were sent home, badly shaken at what had just happened. It was very fortunate no one was injured.

The people who were working there that day were: John Goodall; David Goodall; Henry Robertson; Rose Nimmo; Chris Skeldon; David Brown and the grieve, Joe Leslie. The threshing machine was owned by Wyllie Mills, Haddington and travelled all over the county working at different farms.”